I have been re-watching a really well done drama series about the early days of World War 2 in the RAF called "A Piece of Cake". The squadron's Intelligence Officer is quizzing a visiting Air Commodore about what's going to happen to Poland after the War is won? Considering that Poland was the supposed reason Britain entered the War in the first place but half of it has now been occupied by the Russians! After fumbling for an answer, the blunt response is that "after 25 years in the RAF, the best advice is to never, never, never talk politics in the Mess!"

Well, knowing my Grandfather, as I was lucky enough to, I cannot believe he stuck to this rule. Almost every conversation he had was about politics, specifically , left-wing politics. Some people don't like arguing, especially about politics, but I do and so did he. We spent many evenings in fairly heated conversation putting the world to rights and I miss that very much. He once even invited the Jehovahs Witnesses in to discuss how Religion should become less about faith and more political! After about an hour of 'lively' discussion, they beat a hasty retreat!

From his Log Book, I see that my Grandfather did no flying in December 1942, so I thought it would be a good time to "talk Politics" and try and discover why he was so such a left-wing political animal.

The background to the War, as far as the socialists, including my Grandfather, saw it was that the call to arms was not about Countries, Monarchies, property or power, but to fight against dictatorship, brutalism, intolerance, and militarism. These young socialists had seen what relying on Capitalist markets had done to their fathers and mothers, during the 30's Great Depression, and wanted instead a planned future along the lines of the 5 year plans that the Soviets had adopted.

We are much more cynical these days about the power of Propaganda, despite the fact that we still too often fall in line with the 'news ' that we are fed. But there is no doubting that there was a general left-wing air during the war, with 'everyone in it together' rather than the 'no such thing as Society', 'me first' attitude that we are being forced into today. Thank you Margaret!

One of the most powerful forces for Socialism and the working class in Britain during wartime in Britain was the weekly "Postscript" broadcasts by J. B. Priestly, which drew audiences of 16 million; only Churchill was more popular with listeners. He was brought in by the BBC to counter broadcasts by William Joyce, "Lord Haw-Haw" and was a great advocate for a "new order" after the war where "community is more important than property and power". His memory of how badly the returning Tommies were treated after the First World War fired him up to make sure this would not be allowed to happen again and Britain would become a "land fit for heroes". He was eventually taken off air because the Conservatives, including Churchill, were worried about his socialist views. There is a good radio documentary on J. B. Priestley on BBC Archive on 4.

The war in Britain meant that suddenly everyone was needed. An unemployment rate of nearly 1.5 million in 1939 was banished with people needed for war work in factories or to join the forces. Indeed there was such a huge need for people that women were also called up and were working in all the same trades as the men by the end of the war except for actual combat.

Many women enjoyed going out to work so much, that they didn't want to go back to just "being the little wife at home" after the war. They opened many doors that the next generation of women jumped through.

Union membership, always used as a barometer of left-wing sympathy, rose from 4.5 million before the war to 7 million by it's end.

All this had to be paid for somehow, and even the rises in taxes, especially to corporations and on dividends, were applauded by the socialists due to their desire for more financial redistribution and hate of profit at the working man's expense.

The need to boost morale through propaganda and make everyone feel part of the war was taken right into the kitchens of every household, with the appeal for aluminium to build aircraft.

Well, knowing my Grandfather, as I was lucky enough to, I cannot believe he stuck to this rule. Almost every conversation he had was about politics, specifically , left-wing politics. Some people don't like arguing, especially about politics, but I do and so did he. We spent many evenings in fairly heated conversation putting the world to rights and I miss that very much. He once even invited the Jehovahs Witnesses in to discuss how Religion should become less about faith and more political! After about an hour of 'lively' discussion, they beat a hasty retreat!

From his Log Book, I see that my Grandfather did no flying in December 1942, so I thought it would be a good time to "talk Politics" and try and discover why he was so such a left-wing political animal.

The background to the War, as far as the socialists, including my Grandfather, saw it was that the call to arms was not about Countries, Monarchies, property or power, but to fight against dictatorship, brutalism, intolerance, and militarism. These young socialists had seen what relying on Capitalist markets had done to their fathers and mothers, during the 30's Great Depression, and wanted instead a planned future along the lines of the 5 year plans that the Soviets had adopted.

We are much more cynical these days about the power of Propaganda, despite the fact that we still too often fall in line with the 'news ' that we are fed. But there is no doubting that there was a general left-wing air during the war, with 'everyone in it together' rather than the 'no such thing as Society', 'me first' attitude that we are being forced into today. Thank you Margaret!

One of the most powerful forces for Socialism and the working class in Britain during wartime in Britain was the weekly "Postscript" broadcasts by J. B. Priestly, which drew audiences of 16 million; only Churchill was more popular with listeners. He was brought in by the BBC to counter broadcasts by William Joyce, "Lord Haw-Haw" and was a great advocate for a "new order" after the war where "community is more important than property and power". His memory of how badly the returning Tommies were treated after the First World War fired him up to make sure this would not be allowed to happen again and Britain would become a "land fit for heroes". He was eventually taken off air because the Conservatives, including Churchill, were worried about his socialist views. There is a good radio documentary on J. B. Priestley on BBC Archive on 4.

The war in Britain meant that suddenly everyone was needed. An unemployment rate of nearly 1.5 million in 1939 was banished with people needed for war work in factories or to join the forces. Indeed there was such a huge need for people that women were also called up and were working in all the same trades as the men by the end of the war except for actual combat.

Many women enjoyed going out to work so much, that they didn't want to go back to just "being the little wife at home" after the war. They opened many doors that the next generation of women jumped through.

Union membership, always used as a barometer of left-wing sympathy, rose from 4.5 million before the war to 7 million by it's end.

All this had to be paid for somehow, and even the rises in taxes, especially to corporations and on dividends, were applauded by the socialists due to their desire for more financial redistribution and hate of profit at the working man's expense.

The need to boost morale through propaganda and make everyone feel part of the war was taken right into the kitchens of every household, with the appeal for aluminium to build aircraft.

There is some contention about what happened to all the scrap pots and pans that were collected, with some saying it was just dumped at the end of the war. But it made people feel good about themselves and that they were doing something to help win the War.

There were subsequent appeals to the public sense of community, fair play and good behaviour, including "Make do and Mend"

and rationing food

which were designed to control the behaviour of the population, relying on being seen to 'do the right thing' and 'muck-in' together. The outcome was that despite the threat of attack from Germany, many people thought the War was the best days of their lives, as people were so friendly and community minded. This made a big impact on my Grandfather and may explain why (with his later promotion and command of men in the RAF) he had a strong sense of right and wrong and always took great delight in telling people what to do!

For the socialists, December 1942 was a very important month in politics with the publishing of the Beveridge Report laying the groundwork for the Welfare State.

Interestingly, in trying to give reasons for the British population to fight against Hitler, the coalition Government had brought forward a package of social welfare insurance proposals that had been milling around for some time before. But to show they were giving something back for enduring the war, they provided a fund to benefit the whole of society that would become a cornerstone of the future Labour Party.

|

| Beverage Report to fight Want, Ignorance, Disease, Squalor, and Idleness. |

Those who attack the Welfare State today due to the way it encourages 'scroungers' should note that Idleness was intended to be dealt with also in the Beveridge Report.

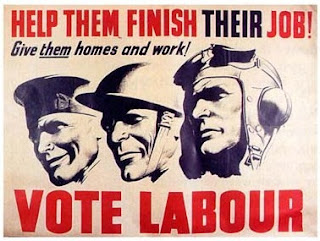

By appealing to the community spirit of people, encouraging them to see the future as better than the past and allowing them to make a valuable contribution to Britain in the fight for freedom from dictatorship, regardless of their class or background, there was a general movement to the left in British politics at the time. This left-wing support was finally cemented at the end of the War with the last and most amazing fact of wartime Britain, when the British people threw out Winston Churchill, the bona-fide hero of the Second World War, and elected a Labour Government.