The year 1942 found my Grandfather, Howard Kelsey, in the relatively peaceful pursuit of training new RAF pilots at Booker airfield, Marlow. Meanwhile the War all around was raging on. The RAF operations in Britain mainly concentrated on attacks on German warships and naval facilities in the Atlantic and North Germany. But with the Japanese sweeping through the Far East, many young RAF pilots lost their lives in the retreat from Malaya and Singapore. I still thank all the Heavens that my Grandfather was still not "On Ops" (flying combat operations) at this stage of the War.

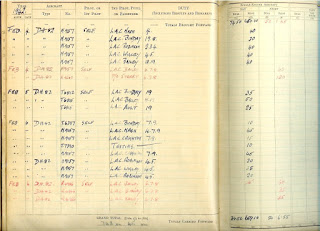

My Grandfather's Log Book for January 1942 shows him continuing to put his pupils through their paces. But there is one interesting entry on Jan 15th, which shows him piloting a Tiger Moth with his brother S/Ldr Kelsey in the Passenger seat!

S/Ldr Richard J Kelsey, later known to me as Uncle Dick, had been commissioned in the RAF in 1936. He joined 213 (Fighter) Squadron at RAF Northolt in 1937, flying Hawker Hurricanes.

Hawker Hurricane

In December 1941 he was promoted to Squadron Leader (Temporary) and the following January found himself being bounced around the sky by his baby brother!

The "Duty" column for their first flight together shows the number 19, which when I refer back to my blog "Sequence of Instruction"(Link) means "Instrument Flying". This was to simulate night flying and was accomplished by pulling a canopy over the pupil so they were in the dark and could only fly using their instrument panel. Obviously the trainer could still see and would avert possible crashes if necessary!

Tiger Moth with night flying hood

I really have no idea why my Grandfather was putting his brother through this test, but perhaps Uncle Dick was learning how to do it, so he could train his own squadron? I do know that he became Chief Flying Instructor at No. 2 EFTS.

The second flight they took has "FSF" in the "Duty" column. Having scoured the RAF acronym websites, I cannot find what this means. Perhaps "Fighter Squadron Ferry", or maybe "Flying Simulator Flight"? If anyone knows, I would be very interested to find out the meaning.

S/Ldr R J Kelsey

Uncle Dick had trouble with his eyesight during the War and had to have special corrective goggles made to enable him to continue in the service. He was involved in a Hurricane crash in March 1939 (Link) and there is a sad piece about him from the Daily Express in August 1939 written by Victor Ricketts - Daily Express Air Reporter;

"SOMEWHERE in Westland I stood at sunset with an R.A.F. fighter pilot who four years ago was passing into the sixth form at a public school. Over us circled a flight of three Hurricanes silhouetted blackly, against the sunset. Inside each of the rumbling fighters sat a war-wise youngster ready to slam his throttle wide open in pursuit of raiding bombers. We two stood and looked up at the fighters, that between them carried enough bullets to kill 10,000 men and the young man with silver wings on his chest said quietly, "No! I am not flying tonight. You see I am going blind."

It was evening, with dew on the airfield grass, camouflaged planes ranged out, a mobile field kitchen with the fragrant smell of hot coffee, and far away, now, the drone of the patrolling fighters. I said, "Oh," rather stupidly.

"They've just taken me off flying," I heard him say. "Both my eyes are going a bit dim. I'll be able to see a bit I think, but flying's finished for me. "I had a Rugger accident a few years ago, got a kick on the back of the head. That started it I think."

You hear things, quietly like that, that beat the films. This same boy was until a little while ago a pilot in a crack fighter squadron. It was his life and very nearly his death. Roaring along on night manoeuvres he had the real-life nightmare of all who fly in the dark—instantaneous and complete breakdown of his engine. At five miles a minute his engine started coming to pieces. Beneath were no lights, only darkness hiding trees hedges, walls, rivers; all the necessary-things to break his neck trying-to land three tons of steel at ninety m.p.h. He took the only way out, through the sliding roof of the dropping fighter . . . with a kick to carry himself clear as he fell into space. Then the moment of suspense, wondering if the silken shrouds of the parachute would open. They did, with a jerk that knocked the breath out of his plummeting body. "Don't you believe that stuff about coming down like thistledown," he grinned. "You hit the ground with a wallop." The fighters were out of sight and we went to a hangar to collect my own parachute ready to take off when our-patrol time came."

Later in the war Uncle Dick was posted to Joint Services Staff college in Haifa, after which he became Officer Commanding RAF station Gaza and then to Air Staff at HQ Middle East in Cairo until the end of the War.

Uncle Dick on the right with his wife, Rose, in the centre.

After the war, Uncle Dick was promoted to Wing Commander and finally retired from the Air Force in 1959. He passed away in February 2010 in Suffolk and I was very pleased to have met up with him again before he died.